Mon Jul 07 23:30:00 UTC 2025: **Summary:**

A new study challenges the long-held belief that the extensive damage to statues of the Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut was solely due to a revenge campaign orchestrated by her successor, Thutmose III. Archaeologist Jun Yi Wong’s research suggests that much of the destruction was likely a result of ritual “deactivation” of the statues and their subsequent reuse as building materials. This practice, common in ancient Egypt, aimed to neutralize the perceived power of the statues before disposal. The study argues that while Thutmose III likely initiated the defacement, the pattern of damage and reuse indicates a broader cultural practice at play, potentially altering our understanding of the relationship between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

**News Article:**

**Hatshepsut’s Statues: Vengeance or Ritual Deactivation? New Study Rethinks Ancient Egyptian History**

**Cairo, Egypt – July 8, 2025** – For decades, archaeologists have attributed the defacement of statues depicting the female pharaoh Hatshepsut to a vengeful act by her successor, Thutmose III. However, a groundbreaking new study published by archaeologist Jun Yi Wong offers a compelling alternative explanation: ritual deactivation and reuse.

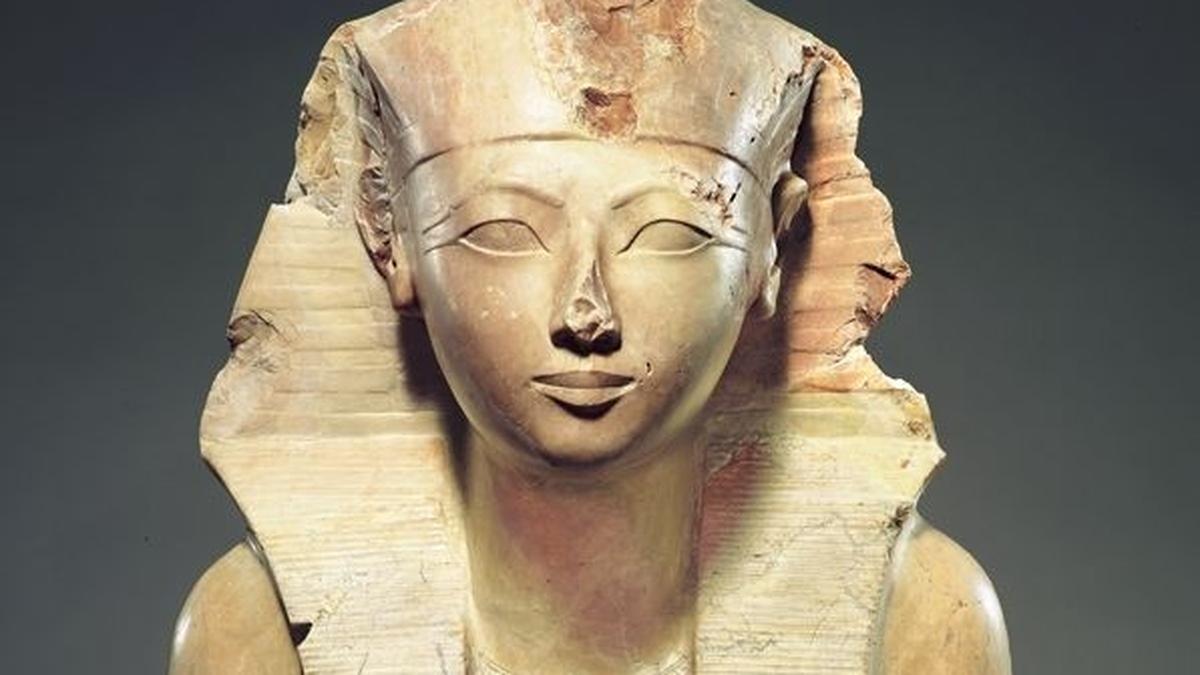

Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt around 3,500 years ago, was a powerful and innovative leader. After her death, many of her statues were found damaged, leading to the assumption that Thutmose III ordered their destruction to erase her legacy.

Wong’s research, re-examining original excavation notes from the 1920s, reveals a more nuanced picture. He found that the statues were not uniformly vandalized. Those found scattered or with significant missing parts showed more extensive facial damage. Statues found relatively intact often had undamaged faces. This suggests that the damage was not solely driven by a desire for vengeance.

“The evidence points towards a practice of ‘deactivating’ statues,” explains Wong. “In ancient Egypt, statues were considered living entities imbued with power. Before disposal, they were ritually broken at key points like the neck, waist, and knees to neutralize this power.”

Furthermore, many fragments of Hatshepsut’s statues were discovered reused as building materials, including in the construction of a stone house. This practice would have further contributed to the damage.

Wong’s findings align with other archaeological discoveries, such as the Karnak Cachette, where hundreds of royal statues were found deliberately deactivated, even those of pharaohs not subjected to post-mortem hostility.

The study challenges the long-held belief that Thutmose III was solely motivated by personal animosity. While he likely initiated some defacement, the ritual deactivation and reuse of the statues suggest a broader cultural practice at play. This new interpretation could significantly alter our understanding of the relationship between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III and shed new light on the complex religious and political landscape of ancient Egypt.